About the author:

Joseph Harmes is an independent writer. Harmes can be reached at [email protected].

The brunt of Hurricane Ida had yet to make landfall south of New Orleans on August 29 when the Sewerage & Water Board (SWB) began alerting that its gravity sewers’ 84 lift stations already were failing, almost eight hours before the storm’s 150 mph winds even arrived to take down power to one million customers.

“This increases the potential for sewer backups in homes,” the SWB warned.

Elsewhere, Ida’s churning surge, wind and rain exposed septic tanks and eroded leach fields, creating health hazards from rural southeast Louisiana to far-flung cities. In Mobile, Alabama, 140 miles east, the county health department warned Ida-related rain and higher tides were causing septic and sanitary sewer overflows containing fecal contamination. Several days later Ida’s remnants dumped several inches on Long Island, New York, enough for authorities to cite spikes in coliform bacteria from leaking urban septic systems as the reason for closing popular swimming beaches. Like Alabama, residents were warned locally harvested fish and seafood could be tainted.

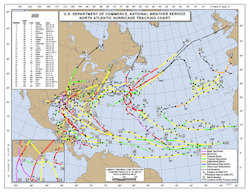

In recent decades, the annual Atlantic hurricane seasons have been arriving earlier, with greater intensity and in greater numbers of storms. The 2005 season was the most active in recorded history. Indeed, the annual pre-designated list of storm names had to be expanded by six Greek letter names. It is best remembered for Katrina — still the costliest U.S. hurricane — which paralyzed New Orleans for weeks and wrecked Mississippi’s coastline.

The six-month 2020 season replaced it as the most active and became the fifth most expensive accompanied by hundreds of deaths. It also marked the fifth consecutive above-average season from 2016 onward. Twelve storms landed on U.S. coastlines. Hurricane Iota, in November 2020, was the latest-forming Category 5 on record.

The 2005 season recorded only five storms but was not insignificant: one was Category 5 Andrew, which left parts of Miami-Dade County and the Florida Keys unrecognizable.

Recovering From Katrina

Ida struck on the 16th anniversary of Katrina, which brought disaster to Kiln, Mississippi, about 58 miles northeast of New Orleans. Katrina’s eye made its final landfall on Kiln (pop. 2,250), which suffered some of the storm’s most intense damage, including the total destruction of its residents’ wastewater disposal systems, consisting entirely of septic tanks. Tapping newly available state and federal recovery funds, Kiln dedicated $20 million to fund a long-desired sewer collection system and wastewater treatment plant.

Kiln’s challenges led it to the All-Terrain Sewer (ATS) a pressure sewer system manufactured by Environment One Corp. of Niskayuna, New York, rather than a gravity, septic tank effluent pumping (STEP) or vacuum system for 1,000 customers scattered across the low wetlands and undulating landscape of a 25-sqare mile service area. Additionally, there were several significant water bodies to cross as well as major state highways that limited open cut excavation.

“[The ATS] won out on cost feasibility over the gravity system and the vacuum system had too many geographic and topographic issues to overcome,” said Geoffrey F. Clemens, P.E. and president of Compton Engineering, Inc. in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. “The STEP system was a relatively competitive concept, but with the cost of a major treatment plant as a given, not as economically feasible.”

The Vulnerable Gravity Sewer

An estimated 800,000 miles of public gravity sewers lay hidden in the U.S., and they are in vast need of upgrades. The U.S. EPA estimates at least $271 billion is required for current and future wastewater infrastructure over the next 25 years.

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) — whose 2021 Infrastructure Report Card rates U.S. wastewater collection and treatment systems a D+ — has said all are susceptible to structural failure, blockages and overflows. Thirty-two states employ frequently overflowing combined sewers (collecting human waste, industrial waste and storm water run-off into a single pipe for treatment and disposal) which the U.S. EPA calls “the largest category of our nation’s wastewater infrastructure that still needs to be addressed.”

Even after a normal rainstorm it is sometimes possible to detect a hint of sewage odor in the air. And a hurricane dismantles the old sewer industry proverb that “dilution is the solution to pollution.”

Hurricane Irma in 2017 exposed decades of growth beyond what Florida’s gravity systems and septic tanks could handle. Without electricity for the pump stations, at least 84 million gallons of wastewater swept into roads, homes, parks and waterways across the state. Angry residents lambasted politicians at local meetings and on social media.

Prior to a large storm or hurricane, crews often are seen clearing debris from gravity sewers and drains. Once the manhole covers stop popping, however, it can be more complicated to restore service. Until full power returned to New Orleans, SWB begged residents to curtail wastewater discharges by taking short showers and — for those with generators — limiting laundry and dishwasher usage. Generators and temporary pumps were dispatched to its lift stations as well as vac trucks to pump down sewerage lines (New Orleans’ storm drains are separate from its sanitary sewer).

In other recovery scenarios, sewers might be choked with sand or may collapse and need rebuilding. Bringing them back online could also entail smoke tests to determine leaks, drying and cleaning pumps and lift stations, fixing electrical systems, testing for toxic chemicals and harmful bacteria and cleaning, repairing and flushing distribution and sewer lines.

When Septic Is Compromised

The U.S. Census Bureau calculates approximately 23% of the country’s estimated 120 million occupied homes depend on septic systems. Florida alone has 2.6 million septic systems — 12% of the nation’s total — not just in rural areas but heavily-populated coastlands. The EPA estimates 40% of the nation’s septic tanks do not function properly and “are responsible for most of the groundwater pollution in the U.S. today.”

Septic has proliferated along the East Coast’s Hurricane Alley since the 1950s with many thousands still buried near shorelines. For builders, it is a quick and cheap infrastructure as they race to keep up with demand (an estimated 40% of the 900 people moving to Florida daily will use septic). Many local governments once considered septic a temporary solution until proper gravity sewers could replace them, but never got around to doing just that: replacing them.

The concept is simple and can be installed for as little as $3,000 per home. A septic system consists of a tank to trap and hold wastewater and solid waste, which is then distributed (designed to leak) into the ground (STEP affixes an electric motor to the tank to pump effluent to a force main in the street). It can work well if there is enough land with the proper soil conditions (no sand, clay or high water tables) for a leach field, but it is quickly compromised when rain or flooding hinder its ability to handle waste.

When a septic tank is inundated, sewage can back up in the home. After a flood, a wait is required before it can accept household wastewater. If it is opened while the soil is saturated, silt and mud might get into the tank. Pumping its contents under wet conditions can cause the tank to pop out of the ground. Flooding washes soil away from the tank and drain field introducing raw or partially treated sewage and bacteria into the yard.

Rapid development of seaside towns into enticing tourist and retirement destinations in recent decades — and the aftermath of hurricanes or even normal storms — has changed minds about what type of sewer might work best for dense residential and business localities as well as resort developments where homes are on large tracts of land and far from force mains or a wastewater treatment plant.

Pressure Sewer Options

“As the island got more urbanized, we were just hearing more and more about the septic issues people were having,” said Pete Nardi, general manager of Hilton Head Public Service District (PSD) in South Carolina. “After the storm, if you’re in a neighborhood where it’s all septic systems, we’ve had folks kind of wondering, okay, my yard looks okay, the trees didn’t rip up my drain field too bad but I’m wondering about my neighbor.”

Hilton Head PSD has a sizable gravity sewer network servicing many of its 19,000 customers and over the years added pressure sewers using centrifugal pumps, which proved to be problematic. Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs were high as level sensors failed repeatedly and the system required repeated replacement. Today, most have been swapped for an ATS from E/One which averages 8 to 10 years between service calls, including no preventive maintenance. By comparison, a septic or STEP system requires regular aftercare like a pump-out by a qualified septic hauler every two to three years, which can cost hundreds of dollars.

The 1-hp progressing cavity design of the E/One pump was modeled specifically for pressure sewer applications. With this pump, sewage is moved regardless of how many individual grinder pumps are operating whereas with centrifugal pumps, too much flow in the line will hit the shut-off head in the pump and the sewage is stagnant until that pressure drops low enough. The ATS increasingly is used to replace centrifugal counterparts.

The pump inside a grinder station — a tank about the size of a dishwasher that is buried in the ground — creates high head conditions and a robust torque, which can propel wastewater through small-diameter, inflow-and-infiltration-free pressurized pipes for a distance of more than 2 miles or even straight up 186 feet to a force main or treatment plant.

High Water Tables

The ATS piping system is not subject to infiltration from groundwater or from surface storm water. With zero infiltration, treatment plants need not be sized to handle wastewater’s peak flow plus storm runoff. In coastal flood settings, it eliminates storm water with high salinity to WWTPs so treatment efficiencies can be more consistent and operating costs decrease.

When Category 4 Hurricane Irma hit the Florida Keys, residents like Florida Atlantic University research professor Brian Lapointe, Ph.D., saw “up to 20-feet of surge,” which flooded his lab on Big Pine Key.

“But one of the great stories that came out of Hurricane Irma was the fact that over the past several years our wastewater infrastructure has been upgraded and relies heavily on (3,000+) All-Terrain Sewers that are sealed systems, unlike gravity sewers,” Dr. Lapointe said. “Because of this, the raw wastewater was contained and this really was a major factor in our water where we didn’t have a lot of raw sewage.”

ATS grinder pumps — pioneered in 1969 and activated daily by more than two million end-users in over 40 countries and U.S. territories — can be installed to force mains or WWTPs with horizontal directional drilling (HDD) under any terrain whether sandy, swampy, or even hardened Hawaiian lava.

A multi-billion-dollar ethane steam cracker project in east Texas chose the ATS for the flat, sandy terrain with high water tables a few miles from the Gulf coast. Subject to frequent storm surge, 2017’s notorious Hurricane Harvey made landfall only 21 miles north. Dewatering for a gravity sewer would have added months of labor and jacked up the budget.

“I don’t care what they say about dewatering, you can’t pump out the ocean and when you cut a hole in the ground here it starts flooding in like you wouldn’t believe,” said Chris Gratton, president and owner of Keys Contracting Service Inc., in Marathon, Florida. “The depth that we can maintain with the All-Terrain Sewer is tremendous for us because the farther we go down, the more water we have. We just run our trench and unroll the piping right up in there.”

Post Hurricane Recovery

Prior to hurricanes, ATS preparedness is minimal and varies from operator to operator. Some utility districts opt for larger tanks like 150-gallon models (or 600-gallons for multi-family dwellings and businesses), which one estimates will store wastewater for four to five days. A study by Stantec Consulting Services for Sarasota County, Florida, calculated that a 900-gallon STEP tank provided only 50 to 100 gallons of additional storage, the remainder always filled with a layer of sludge, effluent and scum.

Steinhatchee, a Gulf coastal community, has installed approximately 485 ATS units to replace polluting septic tanks threatening its reputation as the “Scallop Capital of Florida.”

“If it’s going to get wet, shut it down,” said Mark Reblin, utility manager for Big Bend Water Authority of the community’s philosophy. He and two field technicians drive to each station and turn the power off, a best practice for homes whose residents have evacuated.

The procedure of others is less complicated.

“Let ‘em run until they lose power,” said the operator of another Florida town with 1,400 units.

As long as there is power, they will perform.

“You got 4 or 5 feet of water on top of ‘em and they still worked,” observed Dan DeMaria, Florida Keys fisherman, after Irma.

Following a flood, the ATS should activate as soon as there is power and move wastewater from the tank. Even without power, a homeowner can do this by connecting receptacles from a generator to an ATS alarm panel, a feature inherent to its design.

After Irma, the Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority (FKAA) sent employees to pump ATS stations and told the Key West Citizen that the grinder pump sewage collection systems worked as planned.

Bringing gravity online was not as easy. Irma’s surge wiped out lift stations of what was perceived to be the more robust gravity portion of the $1 billion septic-to-sewer project. Some took up to three months to replace.

“The E/One, of course, is easier to put back into service versus gravity,” said David Mintz, field supervisor for the village of Bald Head Island Utilities in South Carolina, which has approximately 800 ATS units. “As far as equipment goes, it’s very important to have a reliable product that works good for us in our unique situation: Sandy, very stormy, windy, hurricanes, flooding, lots

of flooding.”

A “Smarter” Future

The evolution of the “smart” ATS is bringing a real-time approach to sewers via SCADA devices, which allow operators to monitor not only the performance of every pump in a system but to manipulate flows and remove peak volumes from the network during intense storm events.

Telemetry currently coordinates a network of 15,000 E/One grinder pumps in Mornington Peninsula, Australia, an area vulnerable to short but highly intense rainfall and flash flooding. The FKAA Advanced Telemetry Infrastructure Project is installing remote monitoring systems at its grinder stations, “enhancing the authority’s ability to monitor and maintain the system 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” according to the utility.

“We here on Big Pine Key are blessed with the highest biodiversity in the continental United States, a very unique environment,” Lapointe said. “The ATS in the Florida Keys is a wonderful design. We can put in All-Terrain Sewers and pretty much remove the human sewage footprint.”

About the Author

Joseph Harmes

Joseph Harmes is an independent writer. Harmes can be reached at [email protected].