The Complexities of National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) & Microorganisms

About the author:

Saleha Kuzniewski, Ph.D. is an environmental scientist specializing in remediation and biotechnology research. Dr. Kuzniewski received her Ph.D. in Environmental Science and Public Policy from George Mason University. Kuzniewski can be reached at [email protected].

How much of the chemicals and microorganisms we have in our public water systems is regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)?

Acts, which are laws, are passed by Congress and are written in a set of books called the United States Codes (USCs). Regulations are then issued for the USCs so that the USCs can be enforced and these regulations are in another set of books called the Code of Federal Regulations (CFRs).

What Does the Safe Drinking Water Act Regulate?

The SDWA, also known as 42 U.S.C. § 300f, is enforced by the US EPA through the National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWRs) in 40 CFR 141.

The NPDWRs cover various chemicals including inorganic and organic chemicals in public water systems. They also include microorganisms and parasites, although only selected ones compared to the exhaustive list of chemicals.

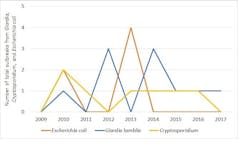

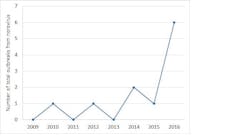

Specifically, these are viruses (unspecified), Legionella (bacteria), total coliform (including fecal coliform) and Escherichia coli (bacteria, also known as E.coli), Giardia lamblia (parasite), and Cryptosporidium (parasite) that have caused outbreaks in drinking water as seen in Figures 1 and 2.

The data for these figures were obtained from the CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS) website. The total number of waterborne outbreaks from Legionella (Figure 1) increased during 2009 to 2017 while norovirus saw an increase during 2014 to 2016 (Figure 2).

What Do These Data Say About Waterborne Disease Outbreaks?

While the number of outbreaks in these two figures are low, there are also some issues about the CDC data in this regard. No data is available from 2018 onward for waterborne disease outbreaks and the 2017 values are zero for outbreaks due to norovirus (Figure 2).

According to the NORS dashboard, a value of zero does not necessarily mean no outbreaks and could also indicate no data was collected that year. Also, the data on the NORS dashboard is selected data as according to the link on “learn more about available data”, the NORS dashboard says (cited): “NORS dashboard does not contain all data reported to NORS” and it provides a contact email address to obtain additional data. Nevertheless, figures 1 and 2 indicate that these organisms, as also regulated in the NPDWRs, are a persistent concern in drinking water.

Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLG) & Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL)

In addition to maximum contaminant level goals (MCLGs), the NPDWR also includes maximum contaminant levels (MCL). The MCLG is the maximum concentration that can exist in drinking water at which no adverse health effect would occur. It is an aspirational concentration level for the chemical and thus not enforceable. On the other hand, the MCL is enforceable and is the maximum permissible level in water. The NPDWRs also include the best available technologies to use to bring a chemical, if it is in violation of its MCL, into compliance with its MCL.

In general, the layout for the regulations of chemicals in the NPDWRs are more straightforward than for microorganisms.

The MCLGs values, listed in § 141.52 of the NPDWRs, are zero for viruses, Legionella, total coliform (including fecal coliform and E. coli), Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium. However while the MCL values are specifically and clearly presented in tables for the chemicals and there are also the best available technologies for most of the chemicals, this is not the case for microorganisms and parasites. The MCLs and the best available technologies to treat them are not mentioned in the NPDWR for most microorganisms except for total coliform.

Total Coliform

The discussion on the MCL for total coliform, in § 141.63 of the NPDWRs, mentions that no more than 5% of the samples per month could test coliform-positive for a water system that collects at least 40 samples per month. If the water system collects less than 40 samples per month, then for MCL compliance, there should be no more than one coliform-positive sample per month.

The best technologies for achieving compliance with the MCL for total coliform, as also mentioned in § 141.63 of the NPDWRs, among maintenance (pipe replacement, repair, flushing program etc.) include filtration and disinfection depending on the drinking water source. Filtration or disinfection is mentioned for surface water and disinfection using chlorine, chlorine dioxide, or ozone is mentioned for ground water.

Cryptosporidium

There is also a section for enhanced treatment for Cryptosporidium (§ 141.700) and other technicalities including for developing disinfection profile for Giardia lamblia and viruses for their 99.9% inactivation (§ 141.709). Also included in the NPDWRs for Cryptosporidium is the microbial toolbox option (§ 141.715 to § 141.722). This is a list of treatment options (known as toolbox options here) that could be used to control the concentration of Cryptosporidium in public water systems. These systems can use one or more of the tools, depending on the criteria also mentioned in this section, to get credit in the form of Cryptosporidium reduction credit.

For example, the use of bag or cartridge filters, provided this use meets the mentioned criteria, gives a maximum of 2 log credit, i.e. credits for 99% reduction of Cryptosporidium. Although the microbial toolbox option is interesting, it is complex to understand and to use by wastewater treatment operators.

Additional Microorganism & Parasite Regulations

The NPDWR is not the only regulation that covers microorganisms and parasites. There are other regulations including the Health Advisory Program (HSA) sponsored by the EPA which serves as an informal guide for drinking water contaminants and is not required to be enforceable.

It is similar to the NPDWR as it covers the same list of microorganisms and parasites and also includes zero values for the MCLGs. It also includes treatment techniques — commonly disinfection and filtration — which are also typically mentioned in the NPDWR. The difference is that the HSA specifies numerical values for MCL compliance for more microorganisms and parasites, more than in the NPDWR.

In other words, it mentions, in numerical values, how much of a particular microorganism or parasite should be removed for the water system to be in compliance with the MCLs.

What About Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) Water Regulations?

Adding to the complexity for the regulations of microorganisms are genetically modified organisms (GMOs). While GMOs are not covered by the NPDWR, they are regulated by the EPA in two Acts: the Federal Insecticides, Fungicides and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). In both of these, GMOs are treated as chemicals, specifically as chemical pesticides in FIFRA and as chemical substances in TSCA.

U.S. EPA Violation Lawsuits

The US EPA has brought lawsuits against cities for violations of the NPDWR and one recent example is USA v. City of NY and NY City Department of Environmental Protection (2019). USA, acting on the request of the US EPA, filed a lawsuit after the City of NY failed to meet the deadline in the US EPA’s Administrative Order to cover the Hillview Reservoir.

The Hillview Reservoir is a part of New York City’s public water systems and was an open storage facility (i.e. this facility was exposed to air, and it did not have a cover on it). Water was treated with chlorine and UV before entering the Hillview Reservoir, and a cover was needed at this reservoir, according to the NPDWR, to prevent recontamination of this water because it was a source of drinking water supply to city residents.

The plaintiff (USA) alleged that the City of NY and NY City Department of Environmental Protection (known as the city in this lawsuit) violated 40 CFR § 141.714 (c) which requires public water systems that store finished (treated) water to either cover the storage facility or treat the discharge from the uncovered water system to the distribution system to comply with the inactivation or removal of virus, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium. The City of NY agreed to settle this federal lawsuit by covering the Hillview Reservoir and to pay the penalty for the SDWA violations.

Challenges to EPA Microbial Contaminant Rules

Cities have challenged the EPA rules on the regulations of microbial contaminants in drinking water in the NPDWR and an example is the 2007 case for the City of Portland v. EPA.

In this lawsuit, the City of Portland and the City of NY challenged the EPA’s requirements to eliminate Cryptosporidium (a parasite) from their drinking water. Among their allegations was that the EPA failed to use the best available science and ignored significant comments on their 2006 rule for the regulations of Cryptosporidium.

Most cities protect their drinking water against Cryptosporidium by filtering their source water using high-tech filters. New York City and Portland did not filter their water in addition to also not covering their reservoirs of finished water (i.e. water that goes directly to consumers without any additional treatment). Portland and New York mentioned in this lawsuit that they took steps to protect their uncovered reservoirs from contamination by Cryptosporidium including using fences to exclude people and animals.

However as the EPA pointed out in this lawsuit, Cryptosporidium could still enter these reservoirs via bird droppings and small animals could get through the fences. The US EPA’s 2006 rule, similar to the 2003 rule, on the regulation of Cryptosporidium in drinking water required all public water systems that did not filter their water to treat their water source for Cryptosporidium in addition to monitoring for it.

In response to the plaintiffs’ allegations, the Court said that the EPA provided ample evidence and adequately responded to comments for their rule on the regulation of Cryptosporidium. The Court also said that even if the EPA’s evidence and comments’ responses in this regard were flawed, it would not have any effect on the respective US EPA’s rule. The Court denied the petition for review by the plaintiffs.

What Does it Take to File a SDWA Lawsuit?

While the above two lawsuits send a clear message that the NPDWR, which are regulations for the enforcement of the SDWA must be followed by all states, a report co-authored by the Natural Resources Defense Council showed that drinking water violations are very common in the United States and these violations are correlated sociodemographically.

Private citizens affected by drinking water violations can file an SDWA citizen suit against any person or entity that violates the SDWA. There is a notice and delay period of 60 days which means that after filing a notice, if within those 60 days, the EPA, Attorney General, or the state is already prosecuting the same violation or begin to do so, then the plaintiff(s) can no longer continue with the lawsuit.

The greatest challenge in the SDWA citizen suit is satisfying the standing requirement, i.e. plaintiff(s) would need to show proof of being reasonably harmed by the drinking water violation. It is easier to show this proof if the violation is evident in the Consumer Confident Report (CCR), a water quality report that community waters systems are required by the US EPA to deliver annually to their customers than without any evidence.

This report discloses the chemicals and their concentrations in the consumer’s drinking water and any of the above-MCL chemicals in this report could be used, when appropriate for lawsuits, to satisfy the standing requirement. However, the CCR is not always useful as there have been instances when harmful chemicals have not reported in it, and one such example is Talbert v. American Water Works Company (2021) where the plaintiffs only got to know about some harmful chemicals in their drinking water from independent testing and not from their CCRs.

Additionally, the CCR is not available for non-public water systems such as private wells and in reality, satisfying the standing requirement is not straightforward in courts as some courts have a heightened view of the standing requirement while others have a relaxed view.

Rosenbrook et al. v. City of Potterville (2019) is an example of the heightened view requirement. In this lawsuit, the Rosenbrooks and two other families alleged that they were exposed to water contaminated by fecal bacteria when they lived at Independence Commons, a manufactured housing community in Potterville, Michigan, near a wastewater treatment plant. They alleged that Independence Commons supplied them with drinking water contaminated with coliform and some of their children suffered from rashes after baths.

The wastewater treatment plant held sewage in open air lagoons and the strong odor of raw sewage in the springs and the summers was reported to the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). The DEQ eventually cited Potterville for violations at its wastewater treatment plant including the failure to submit monitoring reports for discharges in the past. While the former Potterville’s City Manager responsible for this filing was fired, Independence Commons’ owner, Independence Commons Titleholder, LLC sued the plaintiffs’ lawyer, alleging he made a defamatory statement to a newspaper.

While the media report did not specify what the defamatory statement was, it could have been that the plaintiff’s lawyer told the newspaper that private tests of the drinking water from residents at Independent Commons tested positive for coliform. However, water sample taken by Potterville city officials from a single faucet in the community clubhouse tested negative for coliform. Both lawsuits were dismissed, with the class action lawsuit dismissed with prejudice.

There is no public information about these court cases and what is known, as mentioned here, is from news articles. One issue is clear here: water testing from one source is not enough and several water samples from different sources in the community should have been taken to ascertain the accuracy of the results for the coliform test.

What Do Water & Wastewater Operators Need to Succeed?

The regulations of microorganisms in the NPDWRs are complex as are environmental lawsuits as described in this article. The microbial regulations are laid out differently than for chemicals in the NPDWR, which covers different types of public water systems including surface water, making it confusing for people to navigate these regulations. Nevertheless, this calls for education and advocacy for professionals and communities.

Specifically, educators and advocates need to assist wastewater treatment operators and drinking water suppliers in getting familiar with these regulations, including the microbial toolbox (i.e. what is the microbial toolbox, what is meant by the inactivation credit in this toolbox, and how they can use the microbial toolbox), and also provide them with directions in getting the required local and federal support and resources so they can meet these regulations to provide clean drinking water to communities.

Conclusion

The outcome of environmental lawsuits can be discouraging to people and adding to this negativity is the federal standing requirement to prove reasonable harm from the drinking water, which is viewed inconsistently in the courts (i.e. some courts have a heightened view of this standing requirement while others have a relaxed view).

However, having clean water is a basic necessity and the U.S. is among the countries in the world with the cleanest drinking water. People should be encouraged to file lawsuits when they are harmed by contaminants in their drinking water. Advocates need to step in to fill this role: to encourage these people to file lawsuits and to help them navigate the court system. The outcome of environmental lawsuits might seem unfair; however, the courts consider all the requests from the respective parties without prejudice and also apply the laws fairly.

Our state and federal governments are doing their part to regulate public water systems to ensure communities have clean drinking water. Advocates and educators should encourage environmental lawsuits from people harmed by drinking water contaminants, as the more lawsuits there are in Courts, the more aware our state and federal governments would be about the issues with drinking water contaminants and so they could assist in resolving these issues.

We all need to work together to ensure our public water systems consistently provide us with clean drinking water.

About the Author

Saleha Kuzniewski

Saleha Kuzniewski, Ph.D. has authored several publications in the fields of scientific research, biotechnology, and environmental regulations. She is the winner of the 2023 Apex award for publication excellence. She is also the founder of Environmental Remediation & Innovations, LLC. Kuzniewski can be reached at [email protected].