Dartmouth Study Finds that Arsenic Inhibits DNA Repair

Source Dartmouth Medical School

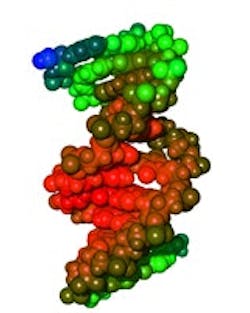

Dartmouth researchers, working with scientists at the University of Arizona and at the Department of Natural Resources in Sonora, Mexico, have published a study on the impact of arsenic exposure on DNA damage. They have determined that arsenic in drinking water is associated with a decrease in the body’s ability to repair its DNA.

“This work supports the idea that arsenic in drinking water can promote the carcinogenic effects of other chemicals,” said Angeline Andrew, the lead author and a research assistant professor of community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School. “This is evidence that it’s more important than ever to keep arsenic out of drinking water.”

The study, which was published online on May 10, 2006 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, examined the drinking water and measured the arsenic levels in samples of urine and toenails of people who were enrolled in epidemiologic studies in New Hampshire and in Sonora, Mexico. Andrew and her colleagues examined the data in conjunction with tissue samples from the study participants to determine the effect of arsenic on DNA repair. To further corroborate their findings, the researchers conducted laboratory studies to examine the effects of arsenic on DNA repair in cultured human cell models.

“The DNA repair machinery normally protects us from DNA-damaging agents, such as those found in cigarette smoke,” Andrew said. “The concern is that exposure to drinking water arsenic may exacerbate the harmful effects of smoking or other exposures.”

Andrew explained that in regions of the U.S. where the rock contains higher levels of arsenic, there is a greater likelihood that drinking water sources contain some potential adverse levels of the toxin. While the levels of arsenic in municipal water systems are regularly monitored, there is no mandated testing of arsenic levels in private wells. This is of particular concern since the regions where arsenic levels are high are in rural regions, such as New Hampshire, Maine, Michigan and some regions of the Southwest and Rockies. Private wells are common in these areas as primary sources of drinking water.

Andrew’s co-authors on this paper are: Jefferey Burgess, Maria Meza, Eugene Demidenko, Mary Waugh, Joshua Hamilton and Margaret Karagas, all from Dartmouth Medical School, the Department of Environmental and Community Health at the University of Arizona or the Department of Natural Resources at the Technological Institute of Sonora, Mexico.

The research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Cancer Institute, the Dartmouth and Arizona Superfund Programs and the American Society of Preventive Oncology.

Source: Dartmouth Medical School