Iowa’s Innovative Approach to Nutrient Loading: The Nutrient Reduction Exchange

About the author:

Tyler Marshall is a principal environmental engineer in the Iowa City office of Stanley Consultants, performing civil and environmental engineering projects since 1998.

|

Read the other articles in this series

|

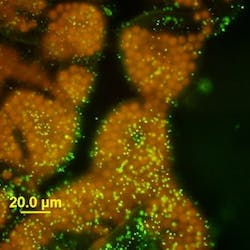

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lists there are 253 harmful algae blooms resulting in lake and beach closures or public health advisories across the country. This year, the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico was measured at nearly 7,000 miles. The problem is getting worse, not better.

The algae blooms are a result of a massive amount of fertilizer nutrients—mostly phosphorous and nitrogen—from farms and lawns that are carried off from storm water runoff into the nation’s streams and rivers. The issue is square in the sights of the EPA, which has long sponsored task forces to study the problem, encouraging states to implement their own programs. The agency has not moved to install mandatory nutrient reduction standards into law; at least not yet.

Nearly half of U.S. states have adopted some type of numeric criteria for phosphorous and nitrogen levels in various types of water. And various governments and industries have attempted non-source treatments, which are at the point of discharge in the form of an industrial facility or municipal water treatment plant.

The problem with source treatment schemes is that they are a finger in the failing dike. It would take an enormous expenditure to treat sources to remove nutrients, while not addressing the non-source root of the problem, namely agriculture. The solution requires a systematic approach at the non-source level.

The Iowa Nutrient Reduction Exchange Program

The state of Iowa, a farming and industrial state, would prefer to avoid adopting numeric criteria for source dischargers of more than a million gallons of water per day. If all the various governments and water authorities had to hit their numbers, it could really hurt. The bedroom community of Iowa City is building a $10 million water treatment plant for 3,300 residents. Iowa City can afford the expense, but many more communities are struggling and would need some type of water excise or additional sales tax.

The State of Iowa has been a participant of the EPA’s Gulf Hypoxia Task Force, which has been looking for solutions to the nutrient problem since 1997. As part of this participation, the state has committed to try to reduce the total mass of nutrients going to the gulf by up to 45%. By meeting this goal as part of a voluntary reduction program, it is hoped that more strict water quality criteria can be avoided. This is the case in some surrounding states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin, who have adopted numeric water quality criteria for both nitrogen and phosphorous.

Should Iowa be pushed into adopting similar criteria, it would hit point source dischargers such as municipal wastewater treatment plants and industrial dischargers the hardest, since the current NPDES permit framework where the new water quality standards would apply do not apply to non-point source dischargers. This would be a significant burden for point source dischargers.

An innovative approach under development by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) in collaboration with the League of Cities, the Association of Business and Industry, and other stakeholders will create such a trading framework. This framework is called the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Exchange (NRE). The NRE is in the final stages of implementation by IDNR, which will require rulemaking to lock in the trading mechanisms and incentives for those who use the program, which should be less burdensome from a regulatory point of view.

IDNR has approved the user-friendly Nutrient Tracking Tool (NTT) for use in calculating the nutrient reductions. This is a web-based tool which allows users to model nutrient runoff through a geospatial interface, using inputs from existing terrain, soil, weather and land use databases. The user can select various conservation practices or engineered solutions for a given project site and simulate the effective nutrient removals which might be available.

These reductions are then validated through review by Iowa State University scientists and registered for credits using the Regulatory In-Lieu Fee and Bank Information Tracking System (RIBITS) database, originally developed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers for tracking wetlands credits. The performance of the selected nutrient reduction practices would need to be periodically inspected and verified for ongoing receipt of credits.

This trading framework will allow for a non-point source conservation practice to be implemented, and credits generated for the reduction in nitrogen and phosphorus entering the watershed. These credits could then be traded to a point source discharger to meet the voluntary nutrient reduction targets that have been added to existing NPDES permits, in lieu of constructing new conventional treatment facilities.

Additional incentives might include longer compliance schedules for meeting nutrient targets, or priority scoring for funding evaluations. The method of nutrient reduction may provide an opportunity for addition of public recreation areas, creation of wetlands and habitat, and reduction in peak flood volumes within a watershed.

Funding For Success & Options for Financing Watershed Projects:

Currently, IDNR allows state revolving loan fund interest payments to be diverted to a sponsored project in or near the community which would address water quality problems. A sponsored project could be selected with a primary aim of reducing nutrients, and the generated credits could either be used directly by the party who registered the nutrient reductions, or they could be traded to another point source discharger within the watershed.

The NRE will create a framework where municipalities and industries can work together with landowners and watershed associations to create a meaningful reduction in the amount of nutrients entering the waterways, while at the same time, saving a significant amount of money compared to conventional treatment techniques. There are also opportunities for larger scale wetlands projects to generate additional income through the creation of wetland mitigation banks, which can sell the credits for each acre of created wetland through the existing wetlands credits system.

On top of the savings, non-monetized benefits include improved soil quality, aesthetics and wildlife habitat, reduced peak floods and the potential for public recreation.

Iowa’s Water Excise Tax, adopted in 2018, is directing $280 million of water utility tax payments for water quality initiatives. The tax has begun to be distributed various water improvement funds, local governments, industrial users and agencies for both point and non-point source projects. This is just one example of creative ways that state governments are funding nutrient reduction projects.

Additionally, the Natural Resources and Outdoor Recreation Trust Fund was created by Iowa voters in 2010 will be funded by an allocation of the first three-eighths percent of any future sales tax increases into water quality projects. This could generate up to $90 million per year would be used to fund projects to improve and protect Iowa’s waterways.

Read More Nutrient Loading & Algae Bloom Articles

- Read Part 1 of this series—Ever Increasing Algae Blooms & Dead Zones Threaten U.S. Waters & Aquatic Life—for more on algae blooms and how nutrient loading is part of their cause.

- Managing Nutrient Pollution

- Cleaning the Chesapeake

- Next up in this three-part series: The watershed-based approach to address non-point source nutrients. Cheaper, more effective, environmentally friendly options. How does the process work and what are the techniques? Read more Jan. 20!