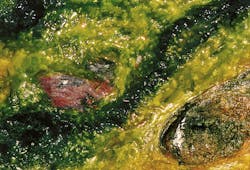

Toxic Algae Threatens Water Nationwide

The algae blooms that shut off Toledo, Ohio’s, drinking water are a growing risk for water resources across the country and are increased by climate change. This summer has seen similar breakouts in Wisconsin, Oregon, Kansas and Maryland, where officials have warned residents about threats to their water.

The rapid proliferation of toxic algae, which can damage human organs, cause neurological problems, rashes, diarrhea, vomiting and nausea, are the consequence of modern development, large-scale agricultural production and, increasingly, changing climate. Their connection was brought into sharp focus this week by Toledo’s algae-bloom linked water crisis.

The country’s harmful algal blooms (HAB)-related water quality problems increased in parallel with growing industrial agriculture and urbanization. Both produce excess nitrogen and phosphorus that algae consume as food. Meanwhile, scientists have also found that existing climate change impacts in the U.S.—higher temperatures, increased precipitation, and prolonged growing seasons—provide increasingly favorable conditions for algal blooms. New York, Ohio and Washington reported eleven freshwater-HAB-associated outbreaks in 2009 and 2010 to the Center for Disease Control. These outbreaks resulted in at least 61 illnesses, two hospitalizations and no known deaths.

This is an urgent problem far beyond Toledo, with studies and reports documenting the risks to the Southwest, the Southeast, the Northwest and beyond.

In the Midwest, climate change has led to more frequent and intense precipitation events. A 2013 report by the National Wildlife Federation on the problem, found that heavy rainfall increases the amount of phosphorous carried into the lake. The report states that the number of heavy precipitation events in Ohio has doubled over the past 50 years, and that runoff has increased 42% since 1995.

Harmful algal blooms and the water quality problems they cause are not limited to the areas surrounding Lake Erie. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources found troubling levels of blue-green algae in Pelican Lake leading the Oneida County Health Department to issue a warning against water contact or use. Moving south, Texas has also struggled in recent years with HABs in a number of the state’s freshwater lakes. The NCA’s Southeast chapter warns “climate change is expected to increase harmful algal blooms and several disease-causing agents in inland and coastal waters, which were not previously problems in the region.”

Droughts may also aggravate the problem. The recently released National Climate Assessment’s (NCA) chapter on water impacts explains that climate change is leading to increased drought frequency and duration. Droughts foster conditions favorable to algal growth because they increase nutrient concentrations and residence times in streams.

Like climate change, the costs of delayed action to address HABs are growing. Initial estimates suggest that cleaning up after the recent algal outbreak has already cost the city of Toledo, Ohio, more than $200,000. At the national scale, a 2009 study by Dodds et al., estimated that freshwater HABs nationwide cost the U.S. economy as much as $2.2 to $4.6 billion annually.

HABs are an issue for every state and climate change is exacerbating the issue.