Advanced Metering: Reducing Non-Revenue Water Loss in Redmond

The state of Oregon wants its utilities to keep non-revenue water (NRW) loss at or below the American Water Works Assn.’s national average of 10% to 15%. Much of this water loss can be attributed to water theft through hydrants or engineers using water to fill dry wells without accounting for it. While many utilities struggle to meet this metric, the city of Redmond, Ore.’s average NRW loss is now consistently around 3%.

Before employing advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) software, Redmond’s billing department would run monthly or quarterly reports that uncovered active accounts with meters registering no water consumption over a specific period of time. These NRW loss accounts were a definite drain on resources, as field technicians were dispatched periodically to investigate and make repairs.

Reducing Downtime

With the old equipment, Redmond could detect some problems but not others. For instance, it could easily find a leaky toilet, but not a dripping pipe connecting to a faucet.

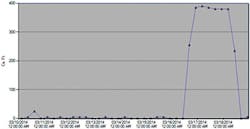

A big challenge was reducing a broken meter’s downtime from months or years—if a broken meter fell through the cracks and went completely undetected—to just a few days. Subsequently, repairing a meter that has been broken for an extended period of time is a double-edged sword: The utility is happy because the repairs reduce lost revenue; however, the customer is confused by the sudden spike in billing.

Another obstacle for Redmond was overcoming infrequent, low-resolution meter reads. Before installing an AMI program, the utility’s legacy data collection units only performed meter readings every 24 hours. As a result, small leaks went undetected because the transmission data provided low-resolution readings that only registered in increments of 50 cu ft, about 350 gal every six hours.

Smart Solutions

Redmond easily can sustain a low water-loss ratio because its AMI system generates detailed weekly reports that allow the utility to quickly and proactively change broken meters and account for all water flowing through the system.

In fact, its AMI data are so detailed that the utility can run hourly consumption reports that pinpoint miniscule leaks, or tell customers how much water they used to irrigate lawns. “More than a dozen times, we’ve alerted customers that their irrigation timers were turning on twice a day,” said Josh Wedding, Redmond’s water operations manager. “They had no idea this was happening.”

Wedding explained that the quicker a broken meter is repaired, the faster the utility can recover the revenue and the less the customer notices the meter was broken—from a monetary standpoint. Generally, if a utility does not have an actual meter read, it may estimate billing that may not be accurate. Of course, customers only want to be billed for the services they are actually using. Because Redmond does not estimate billing, however, customers would only be billed at the base rate for the meter.

Consumers might sometimes believe that more water running through their meters means more money for the utility. Wedding explained that is not the case.

“We bill strictly based on recovering the cost to produce water,” Wedding said. “So it is really just a drain on resources.”

In effect, AMI data can encourage conservation. Studies have shown when utilities provide detailed, comparative analyses, consumers conserve resources and even become competitive about using fewer assets.

An important conservation strategy for large commercial accounts involves upgrading and retrofitting meter registers where possible to get resolution reads down to a tenth of a cubic foot. Ultimately, Redmond believes it is imperative to generate leak detection and total consumption reports and get that information squarely in the hands of its customers, particularly during drought conditions.

“That’s the way we take care of our data,” Wedding said. “That’s how we run our processes here in terms of water accountability.”

Download: Here