Reducing Nitrification Risk

La Verne, Calif., situated in the eastern Los Angeles basin, has seen its fair share of growth and change since it was incorporated as a quiet agricultural town in 1887. Now part of the greater mega-metropolis of Los Angeles, La Verne has a population of more than 33,000 and relies on water both from its own system of wells and from wholesaler Three Valleys Municipal Water District (TVMWD), part of the massive Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

Like many municipalities in Southern California, TVMWD is a chloraminated system. While chloramines provide a more stable and persistent residual disinfectant (and reduced disinfection byproducts), they present challenges to water operators who must carefully balance the ratio of chlorine and ammonia in their water distribution system and vigilantly monitor their system for nitrification.

La Verne routinely monitors its water system for early signs of nitrification—usually indicated by a drop in residual chlorine and an increase in nitrite. When nitrite is measured above La Verne’s action level of 0.05 mg/L in one of its storage tanks, operators will manually add chlorine to arrest nitrification. This process requires one or more operators to transport chemicals to the tank site and manually dose it into the tank.

Adding New Technology Into the Mix

In 2010, La Verne was introduced to the PAX Water Mixer. After installing the mixers in two of its most problematic reservoirs, it saw immediate improvements: “We saw more stable and uniform residual levels in those two tanks,” said Utilities Manager Jerry Mesa.

The mixers also made manual dosing of the tanks much easier. Instead of having to wait until the tank was filling to administer the dose, operators could introduce chlorine right above the mixer, which would distribute the disinfectant throughout the tank.

“The mixers made it much easier to distribute the chlorine in the tank, especially if the tank was rectangular and sharing the same inlet and outlet line,” said Water Supervisor Richard Martinez.

“We were very fortunate to have a number of colleagues in surrounding municipalities share their experiences,” Mesa said. “We didn’t have to reinvent the wheel. We could have easily gone a different direction initially with mixers. But managers from nearby water utilities told us that they had tried different mixing technologies that didn’t work.”

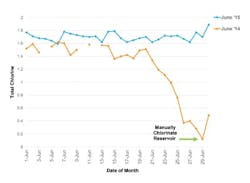

After the initial success at the first two tanks, La Verne added mixers to other tanks where residual levels were inconsistent. While the mixers improved residual stability, La Verne still observed occasional episodes of nitrification in several reservoirs. The aboveground steel 5-million-gal Plateau 2 reservoir in the northern hills above the town was a particular concern. This tank showed higher water temperatures than a neighboring Plateau 1 concrete tank and thus posed a greater risk for nitrification.

In 2013, La Verne water managers were introduced to a new technology that would allow them to respond more quickly and effectively when early signs of nitrification were detected in this tank. The PAX Residual Control System (RCS) is an automated residual monitoring and boosting system that utilizes the PAX Water Mixer to maintain constant disinfectant residual levels within the tank. Housed in either a portable trailer for quick deployment, or in a permanent structure at the tank site, the RCS continuously monitors water quality inside the tank and intelligently boosts the correct proportion of chlorine and ammonia based on the water’s chemistry.

The initial days after the installation were somewhat disappointing. “We were putting a lot of 12.5% hypochlorite solution into that tank and we struggled to maintain a stable residual level,” Mesa said. Operators decided to isolate the tank and change the disinfectant chemistry to free chlorine (a process called breakpoint chlorination) in an attempt to address the anomalously high chlorine demand they were observing. After stabilizing the water at 1.7 ppm of free chlorine, the RCS then added ammonia back into the tank to return the chemistry to monochloramine. After seeing stability return, La Verne put the tank back online, and watched as the RCS continued to maintain stable residual levels.

“After that initial period of effort, the tank is now stable and the RCS is able to maintain a set-point of 1.6 to 1.8 ppm consistently,” Mesa said. “We no longer observe periods of low residual or elevated nitrite.”

Interestingly, water operators report that residual levels stabilized and improved not only in the tank itself, but also in much of the surrounding distribution system. Once the permanent installation was completed and the RCS was turned on, operators again observed a period of a few weeks when elevated demand was observed. “It has been working pretty well since then,” Martinez said.

“Investing in this technology is a no-brainer,” Mesa said. “It’s a fix that saves my staff time and cost.”